Issue 26: Intimate Partner Violence Against Immigrant and Refugee Women

This issue on immigrant and refugee women will:

|

View Printable PDF

View Printable PDF

View Plaintext PDF

Immigrant and refugee women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV) face numerous barriers and challenges to disclosing and reporting abuse, accessing supports and services, and navigating intersecting legal processes and social support systems.[1]

“Not all women are oppressed and/or subjugated in the same way or to the same extent, and violence against women and its impact are not borne equally by all groups of women.”[2]

It is essential to recognize that immigrant and refugee women hold many intersecting identities (e.g. sex, gender, education, race/ethnicity, sexuality, ability, religion). These intersections will greatly impact not only their vulnerability to intimate partner violence, but also their experiences and the system’s responses to them (e.g. justice, housing). Women who are marginalized in multiple ways and who face structural violence by different systems of discrimination have difficulty being believed, accessing support, and finding safety.

Narratives throughout this issue are used with permission. We are grateful to the researchers and the women who shared their experiences.

How Racism and Sexism Intersect in the Context of Gender-Based Violence

An intersectional approach indicates that to prevent violence against women, we must challenge racism and other forms of discrimination that also affect their lives. Racism is a common form of violence that is experienced by women from immigrant communities in Canada who are racialized.[3] When looking at gender-based violence against immigrant and refugee women, it is critical to see the different ways in which racism and sexism intersect and influence their lives. For instance, dominant discourses of immigrant and refugee women and domestic violence tend to “culturalize” violence, seeing it as a product of cultural conflict rather than structural inequality.[4] As a result, the “othering” that occurs with gendered socialization and racialization exacerbates the complex and intersecting forms of violence that women of colour experience.[5]

Furthermore, many immigrant and refugee women’s experiences of violence and gender inequality are interlinked with their experiences of racism and discrimination. Examples include: publicly abusing a woman wearing a hijab, underpaying migrant women domestic helpers, having a high proportion of immigrant and refugee women in low-paying jobs and precarious work, and racially derogatory sexual harassment.[6] The relationship between violence against women and racism can also be noted in forms of detention and deprivation of liberty and freedoms through state-based mechanisms and policies that are based on race or immigration status. Discrimination and fear of racism can impede a woman’s access to intervention and prevention programs, information, social networks, services, use of spaces or support. As a result, some women feel less safe, less respected, and like they do not belong in the broader community.[7]

The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw - Watch this video on YouTube (available with subtitles)

MUST-READ

Rivers of Hope: A ToolKit on Islamophobic Violence by and for Muslim Women

This toolkit, developed by Sidrah Ahmad, Coordinator of the IRCNFF Campaign at OCASI, is a resource created by and for Muslim survivors of Islamophobic violence. It contains research, real-life stories, resources for survivors, and poetry by Muslim women.

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives”

- Audre Lorde

Challenging Misconceptions about Violence in Immigrant and Refugee Communities

The rate of IPV in immigrant and refugee communities is not known.

Findings on prevalence rates of IPV among immigrant women have been inconclusive. Community-based studies of IPV among immigrant women indicate high rates of abuse.[8] In contrast, several population-based studies from both Canada and the U.S. suggest that rates of IPV are lower among immigrant women compared with nonimmigrant women.[9] Inconsistent prevalence rates are attributed to a range of factors (e.g. measurement methods, access).

There is no honour in violence perpetrated against women and girls, in any community.

Violence against women can occur in all cultures, races, and societies. Coverage of supposed “honour killings” perpetrated by men from immigrant communities against female family members are rationalized as redress for dishonouring the family. Regardless of the alleged rationale, the killing of a woman or girl is femicide. The term femicide does not separate women and girls into distinct groups based on race, culture, or religion and rejects the notion that Western society is not patriarchal.[10]

In all societies, gender inequities are linked to increased violence against women.

Women may be relegated to specific duties and roles and may be oppressed by state or religious laws, or the abuser’s misuse of religion as a way to get power and control. This does not mean that all women themselves are passive or submissive. Violence against women is socially constructed and reinforces the inequitable distribution of power between men and women in society.

Experiences of Violence

Immigrant and refugee women face many of the same types of intimate partner violence as other women. This includes:

- Physical violence (e.g. hitting, slapping, choking, punching, kicking, withholding hormones for gender transition, forced public displays of affection that ‘out’ a partner)

- Sexual violence (e.g. sexual assault, refusal to use protection, forced abortions, using gender roles to control what a partner does sexually)

- Emotional or psychological violence (e.g. isolation from others, creating fear, name-calling, threatening to ‘out’ partner’s sexual orientation, abuse of service or companion animals)

- Financial or economic violence (e.g. controlling access to finances and bank accounts, withholding money, threatening to ‘out’ partner to employer)

- Forced marriage (e.g. forcing women or girls into a marriage without their consent)

- Neglect (e.g. withholding food, care, medication, service animal)

- Electronic violence (e.g. bullying, using electronic devices and social media to monitor or intimidate)

Immigrant and refugee women also face additional types of violence such as immigration-related abuse through threats and violence by their partners. A woman’s immigration status not only heightens her vulnerability to violence but it can also exacerbate the nature of the violence she experiences.[11]

For example:

- Immigrant women with status can face manipulation by their partner in ways that are tied to their newcomer experience. For example, they may be prohibited from learning English or French, or from working, which further isolates them.

- Non-status women face extreme vulnerabilities as they do not have any legal status. They are more reluctant to call the police as they fear deportation, loss of their children.

- Refugee-claimant women may not be aware that they can separate their refugee claim from their abusive partner during the refugee process. They may be told by their partners that they can only receive refugee status if they remain in the relationship.

RELATED RESOURCE

Race, Gendered Violence and the Rights of Women with Precarious Immigration Status (2017)

This training toolkit developed Deepa Mattoo at the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic provides information on issues affecting racialized women with precarious immigration status in Canada by exploring the relationship between race, gender, and immigration status. Click here to read Legal Director Deepa Mattoo’s reflection on this work.

Factors that Contribute to Risks and Vulnerabilities Associated with IPV in Immigrant and Refugee Communities[12]

- Post-migration strain and stigma

- Stress associated with migration

- Geographic and social isolation

- Changes in husband and wife’s socioeconomic statuses

- Power imbalances between partners

- Change in social networks and supports

- Loss of culture, family structures, and community leaders

- Economic insecurity resulting from non-recognition of professional/educational credentials

- Acculturation level

- Change in gender roles and responsibilities

- Unresolved pre-migration trauma

“I think everything changed a lot. My husband had job in [home country]. We had a apartment. We feel comfortable. We feel confident about that and I definitely I had a job [chuckle] at that time. I feel in the equal. After we moved to Canada, my husband English is not very good. It’s hard to find a job for him. I think he feel so upset about that and he feel wasn’t used to work, I don’t know. Not confident.”[13]

“He took all this attitude with me because I’m immigrant and I didn’t know nothing about his culture. I didn’t know nothing about my right and he confuse me that I didn’t have any rights because I just landed immigrant, I am not citizen.”[14]

Barriers to Reporting or Disclosing Violence and Seeking Help

There are multiple and intersecting barriers that immigrant women face in accessing help. These barriers include those encountered by non-immigrant and refugee women, as well as barriers related specifically to the immigration context.

They include:[15]

- Fear of loss of children (e.g. apprehension, deportation, divorce)

- Discrimination and racism within service delivery system

- Limited knowledge about laws and rights & domestic violence services

- Geographic, social, and cultural isolation

- Fear of deportation due to precarious immigration status

- Social stigma related to disclosure of domestic violence

- Language barriers and lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate services that are easy to access

- Economic exclusion due to lack of recognition of credentials

- Lack of coordinated services

- Lack of accessible shelters (e.g. physical barriers; inadequate provision of spiritual, cultural, or religious needs)

- Lack of access to attendant care and sign language interpretation for women who are living with disabilities or for Deaf women

- Collectivist cultural beliefs that support keeping the family together and not disclosing “private” matters

RELATED RESOURCE

A Reflection on Violence (2018)

Notisha Massaquoi, Executive Director of Women’s Health in Women’s Hands, shares her perspective on the unique circumstances and barriers faced by racialized women and trans clients who experience gender-based violence. Click here to read the full reflection piece.

In Their Own Words…

“I live at my ex’s place, but it’s not because I like living there. It’s just because of financial reasons. Yeah, because, trust me it’s not easy to start life here from scratch. When I came, my expectations were quite different from reality. I thought I was coming to a land of milk and honey, but things turned out differently. Yeah, my husband was abusive and it wasn’t good.”[16]

“No papers. […] you don’t have family, you don’t have nothing. And the people that you go through with, the people that’s supposed to help you is… you are afraid to tell people what’s going on because you don’t know that will be safe for you, so I wait for a long time.”[17]

“I was in a relationship waiting and living [in] hell because I didn’t know that we have all this kind of supports.”[18]

“So I go to meet her [abusive partner’s probation officer] and I am sitting in front of her, and she’s like, ‘I don’t understand your culture, and this is all because of your culture and your religion.’ ….’Do you even understand the law? Do you even speak English? Do you get these things? Like you just got married to him for money and to come to Canada, right?”[19]

“Discrimination leaving an abusive relationship to begin with and now if you add on that she’s an immigrant woman, a lot of landlords have a lot of stereotypes about immigrant women. A lot of landlords don’t want to deal with somebody who doesn’t speak English as a first language. A lot of landlords have judgments about different ways of parenting, about stereotypes about food smells, or—it’s awful.”[20]

Immigrant and Refugee Women are Resilient

It is important to note that every woman is more than her experience of violence. Women-centred approaches recognize and build on strengths in order to empower women and support them in resisting structural violence. Some strengths critical to strengths-based approaches are:

- Immigrant and refugee women informally support each other, outside of social service structures.

- Immigrant and refugee women often have multiple language skills.

- Immigrant and refugee women develop creative ways to build community, become economically independent, and heal from their experiences of violence.

- Immigrant and refugee women are leaders in the anti-gender-based-violence movement in Ontario.

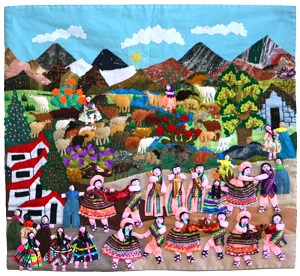

Hilos Resilientes at the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic

Hilos Resilientes is a third-stage arpillera (threedimensional appliqued textiles of Latin America that originated in Chile) group for Spanish-speaking women who self-identify as Latina. This form of sewing brings women together “in a circle of care, gives them a sense of belonging to a larger community that provides hope and meaning while creating the conditions for activism and social justice.”[21] At the same time, these gatherings provide a space for “belonging, healing, and resistance.”[22] For instance, as sexual abuse of women and children in Canada remains “unspoken, minimized, and denied”[23], there is an inherent demand for women to be silent. Hilos Resilientes provides an outlet for women to speak out, through their words stitched onto the cloth or with scraps of fabric, embroidery, yarn, threads, and crocheting. Read more here.

Hilos Resilientes is a third-stage arpillera (threedimensional appliqued textiles of Latin America that originated in Chile) group for Spanish-speaking women who self-identify as Latina. This form of sewing brings women together “in a circle of care, gives them a sense of belonging to a larger community that provides hope and meaning while creating the conditions for activism and social justice.”[21] At the same time, these gatherings provide a space for “belonging, healing, and resistance.”[22] For instance, as sexual abuse of women and children in Canada remains “unspoken, minimized, and denied”[23], there is an inherent demand for women to be silent. Hilos Resilientes provides an outlet for women to speak out, through their words stitched onto the cloth or with scraps of fabric, embroidery, yarn, threads, and crocheting. Read more here.

RELATED RESOURCE

Telling our Stories: Immigrant Women’s Resilience (2017)

A one-of-a-kind graphic novel, developed by OCASI, and written by immigrant women to support immigrant women by sharing stories of community support and engagement in situations of violence for newcomer women. View the graphic novel here.

Recommendations for Supporting Survivors

FOR SERVICE PROVIDERS

Immigrant and refugee women benefit from many of the promising practices intended for all women experiencing violence. Specific considerations when working with immigrant and refugee women are included below.

SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

- Ensure the programming at your agency does not ask for proof of legal status in Canada in order to access services. If you require ID to track numbers for the purpose of reporting to funders, create alternatives so that you can serve non-status clients who are living with VAW.

- Provide resources and supports that are in the woman’s language, or access to professional interpreters who will keep confidentiality.

- Employ front-line workers that reflect immigrant and refugee communities; however, do not assume that women will always want to connect with a member of their specific community.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

- Use a trauma-and violence-informed model at your agency. Assume that any woman who walks through your doors may have faced violence. Do not force women to share an abuse narrative before they are able to access supports.

- Be mindful of multiple traumas the client may have faced prior to the current situation, such as surviving war or child abuse.

- Create safe spaces for immigrant and refugee women to connect and share with each other and heal. These spaces can be themed around art, cooking, or other activities. Such spaces provide important avenues for relationship building that can then lead to disclosures of situations of abuse, and access to supports.

- Use a woman-centered approach. Take the lead from what she is asking for and what her immediate needs are, rather than imposing a plan of action.

- Address the holistic concerns of the woman living with violence, such as income security and childcare.

- Use an anti-racist and anti-oppression approach. Do not blame the client’s race, culture, ethnicity, or religion for the abuse they are facing. This is not about “rescuing” her from her culture.

- Carry out safety planning with the support of professional VAW services, so that the risk to the woman’s safety can be assessed and supports put in place.

- When referring a woman to a shelter, investigate whether the shelter is ready to accommodate her cultural needs, and follow-up around her experience at the shelter.

- Regularly break down stigma around issues of abuse at your agency. Hold workshops and events that raise awareness about abuse and how to access support.

FOR POLICY MAKERS

When creating policies to address violence against immigrant and refugee women, it is Important to:

- Include a race and gender analysis;

- Include the needs of migrant workers, international students, and women without legal status;

- Include the needs of LGBTQAI immigrant and refugees;

- Include the needs of immigrant and refugee women who may live with disabilities and deaf women;

- Advocate for change in areas of immigration law that create vulnerability to VAW;

- Advocate for change in areas of income security and affordable housing that create vulnerability to VAW;

- Advocate for language-specific and community-led projects to challenge VAW in specific ethno-cultural communities; and

- Avoid scapegoating or marginalizing immigrant and refugee communities through policy language or recommendations.

These recommendations were compiled from the #UsToo Roundtable on Building anti-VAW Movements in Immigrant and Refugee Communities, co-hosted by OCASI and the Barbra Schlifer Clinic on March 2, 2018.

RELATED RESOURCE

Enhancing Culturally Integrative Family Safety Response in Muslim Communities (2016)

This new volume examines the Culturally Integrative Family Safety Response (CIFSR) model that is being used in London, Ontario by the Muslim Resource Centre for Social Support and Integration. The model is created to support immigrant and newcomer families from collectivist backgrounds with issues related to pre-migration trauma, family violence, and child protection concerns.

RELATED RESOURCE

The Building Supports project is a three-year community-based project by the BC Non-Profit Housing Association, BC Society of Transition Houses, & the FREDA Centre for Research on Violence Against Women and Children. The focus of the project is to understand the barriers to accessing secure and affordable housing for immigrant and refugee women leaving violent relationships. The project has produced a promising practices guide now available online, policy recommendations, a public awareness campaign, and an intersectional policy analysis of immigration/settlement, housing, and health sectors. View this resource.

Preventing Violence in Immigrant and Refugee Communities

To stop violence against immigrant and refugee women before it begins, requires addressing the underlying gendered and structural drivers of violence in society. Below are some key components for planning meaningful violence prevention initiatives for immigrant and refugee communities:

|

WHAT YOU NEED TO DO |

WHAT IT CAN LOOK LIKE |

|

Give immigrant and refugee communities ownership over prevention strategies and activities in their communities. |

|

|

Role model equitable, collaborative, and meaningful relationships with all partners and participants. |

|

|

Support, involve, and answer to immigrant and refugee women and women’s leadership. |

|

|

Focus on gender inequality at the institution, systems, and policy level. |

|

|

Ensure other forms of social inequality and disadvantage are being addressed. |

|

|

Commit to listening, learning, evaluating, and generating evidence. |

|

ADAPTED FROM:

Working with Immigrant and Refugee Communities to Prevent Violence Against Women (2017)

In this guide, Jasmin Chen focuses on preventing violence against women in immigrant and refugee communities in Australia by working towards gender equality and addressing key drivers of violence against women. View the guide.

PLEASE EVALUATE US!

Let us know what you think. Your input is important to us. Please complete this brief survey on your thoughts of this issue: https://uwo.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_5gulkP0DOquaH77

THIS ISSUE IS A COLLABORATION BETWEEN:

- Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI)

- Learning Network

WRITTEN BY:

- Jassamine Tabibi, Research Associate, The Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

- Sidrah Ahmad, Coordinator for the Immigrant and Refugee Communities Neighbours, Friends and Families Campaign at the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants

- Linda Baker, Learning Director, The Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

- Dianne Lalonde, Research Associate, The Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR THE INPUT AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF:

Fran Odette, Independent Consultant

GRAPHIC DESIGN:

Elsa Barreto, Multi-media Specialist, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

SUGGESTED CITATION:

Tabibi, J., Ahmad, S., Baker, L., & Lalonde, D. (2018). Intimate Partner Violence Against Immigrant and Refugee Women. Learning Network Issue 26. London, Ontario: Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. ISBN # 978-1-988412-24-5

CONTACT US!

www.twitter.com/learntoendabuse

www.facebook.com/TheLearningNetwork

Contact vawln@uwo.ca

[1] Han, J. H. J. (2009). Safety for immigrant, refugee and non-status women: A literature review. Ending Violence Association of British Columbia, Vancouver, Mosaic, & Lower Mainland Multicultural Family Support Services Society. (2011). Immigrant women’s project: Safety of immigrant, refugee, and non-status women.

[2] Yuval-Davis, N. (1997). Gender & Nation. London: Sage Books, p.8.

[3] Jiwani, Y. (2005). Walking a Tightrope: The many faces of violence in the lives of racialized immigrant girls and young women. Violence Against Women, 11(7): 846-875. doi:10.1177/1077801205276273

[4] Razack, S. (2000). Looking white people in the eye: Gender, race, and culture in courtrooms and classrooms. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442670204

[5] Ibid.

[6] Chen, J. (2017). Working with immigrant and refugee communities to prevent violence against women. Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health. Melbourne.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Lee, Y and Hadeed, L. (2009). Intimate partner violence among Asian immigrant communities: health/mental health consequences, help-seeking behaviors, and service utilization. Trauma Violence Abuse 10(2): 143-70.; Hurwitz, E.J., Gupta, J., Liu, R., Silverman, J.G., and Raj, A. (2006). Intimate partner violence associated with poor health outcomes in U.S. South Asian women. J Immigr Minor Health 8(3): 251-61.; Lee, J., Pomeroy, E.C., and Bohman, T.M. (2007). Intimate partner violence and psychological health in a sample of Asian and Caucasian women: the roles of social support and coping. J Family Violence 22(8): 709-20.

[9] Runner, M., Yoshihama, M., and Novick, S. (2009). Intimate partner violence in immigrant and refugee communities: Challenges, promising practices and recommendations. Princeton, NJ: Family Violence Prevention Fund, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Hazon, A., and Soriano F.I. (2005). Experiences of intimate partner violence among U.S. born, immigrant and migrant Latinas. Lown, E.A. and Vega WA. (2001). Prevalence and predictors of physical partner abuse among Mexican American women. Am J Public Health 91:441–5.; Sorenson, S.B. and Telles, C.A. (1991). Self-reports of spousal violence in a Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white population. Violence Victims 6: 3–15.; Cohen, M.M. and Maclean, H. (2003). “Violence against women.” In: Desmeules M, Stewart S, Kazanjian A, Maclean H, Payne J, Vissandjée B, editors. Women’s health surveillance report: a multidimensional look at the health of Canadian women. Ottawa (Ontario, Canada): Canadian Institute for Health Information, p. 45-7.

[10] Canadian Council of Muslim Women. (2012). CCMW Position on Femicide (Not Honour Killing).

[11] Hass, G. A., Ammar, N., and Orloff, L. (2006). Battered Immigrants and U.S. Citizen Spouses. Washington, DC: Legal Momentum, Immigrant Women Program.

[12] Bui, H. N. (2003). Help-seeking behavior among abused immigrant women: A case of Vietnamese American women. Violence Against Women, 9(2): 207-239. doi:10.1177/1077801202239006; Raj, A., & Silverman, J. (2002). Violence against immigrant women. The roles of culture, context and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 8(3): 367–398; Smith, E. (2004). Nowhere to turn? Responding to partner violence against immigrant and visible minority women. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.; Guruge, S. and Humphreys, J. (2009). Barriers affecting access to and use of formal social supports among abused immigrant women. Can J Nurs Res 41(3): 64-84; Guruge, S., Kanthasamy, P., Jokajasa, J., Wan, Y.W.T., Chinchian, M., Refaie-Shirpak, K., et al. (2010). Older women speak about abuse and neglect in the post-migration context. Women’s Health and Urban Life 9(2): 15-41.

[13] Thurston, W. E., Roy, A., Clow, B., Este, D., Gordey, T., Haworth-Brockman, M.,… Carruthers, L. (2013). Pathways into and out of homelessness: Domestic violence and housing security for immigrant women. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 11(3): 287. doi:10.1080/15562948.2013.801734

[14] Ibid.

[15] Hyman, I., Forte, T., Du Mont, J., Romans, S., and Cohen, M. (2006). The prevalence of intimate partner violence in immigrant women in Canada. American Journal of Public Health, 96: 654–659; Guruge, S., Refaie-Shirpak, K., Gastaldo, D., Hyman, I., Zanchetta, M., and Sidani, S. (2010). A meta-synthesis of post-migration changes and their effects on marital relationships in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101(4): 327– 331; Hyman, I., Mason, R., Guruge, S., Berman, H., Kanagaratnam, P., and Manuel, L. (2011). Perceptions of factors contributing to intimate partner violence among Sri Lankan Tamil immigrant women in Canada. Health Care for Women International, 32(9): 779-794. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.569220; Du Mont, J., Hyman, I., O'Brien, K., White, Meghan E., Odette, F., and Tyyskä, V. (2012). Factors associated with intimate partner violence by a former partner by immigration status and length of residence in Canada. Annals of Epidemiology, 22(11): 772-777. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.09.001; Guruge, S. and Gastaldo, D. (2008). Violencia en la pareja e inmigración? Cómo ser parte de la solución? Presencia, 4(8). Retrieved from http://www.index-f.com/presencia/n8/p8801.php; Cottrell, B. (2008). Providing services to immigrant women in Atlantic Canada. Our Diverse Cities. Metropolis Canada. Guruge, S., Khanlou, N., and Gastaldo, D. (2010). Intimate male partner violence in the migration process: Intersections of gender, race and class. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1): 103-113. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05184.x

[16] BC Society of Transition Houses. (2015). Phase 1 Final Report: Housing access for immigrant and refugee women leaving violence. Vancouver, BC: BC Society of Transition Houses. Retrieved from: https://bcsth.ca/publications/building-supports-phase-1-report/, p.14.

[17] Ibid, p. 12.

[18] Ibid, p. 13.

[19] Ahmadzai, Masiya. (2015). A Study on Visible Minority Immigrant Women's Experiences with Domestic Violence. Social Justice and Community Engagement 14. Retrieved from: https://scholars.wlu.ca/brantford_sjce/14

[20] BC Society of Transition Houses, 2015, p. 16.

[21] Gana, C. and Jenkins, L. (2016). Resilient Threads Telling Our Stories Hilos Resilientes Cosiendo Nuestras Historias. Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America's 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah. GA. October 19-23. 2016, p. 281.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.