.

Learning Network Knowledge Exchange Summary Report

Violence Against Women & Traumatic Brain Injury

Novotel Hotel, Toronto ON

March 7, 2019

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Report Prepared by:

- Robert Nonomura, Research Associate, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

- Linda Baker, Learning Director, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

- Dianne Lalonde, Research Associate, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Graphic Design by:

- Elsa Barreto, Digital Media Specialist, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against

CREVAWC Administrative and Support Team:

- Barb Potter, Maly Bun-Lebert, Sara Straatman, and Karim Omar

Suggested Citation:

Nonomura, R., Baker, L., & Lalonde, D. (2019). Knowledge Exchange Report: Violence Against Women and Traumatic Brain Injury. London, Ontario: Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. ISBN: 978-1-988412-32-0

©2019 Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

Special thanks are also in order to Dr. Gloria Alvernaz Mulcahy, Associate Researcher at CREVAWC. Gloria opened and closed the day’s proceedings by leading the group in an Indigenous song celebrating the resiliency, bravery, and strength of women who have experienced partner violence. Her voice, and the voices of all who joined in, set a tone of gratitude to the Indigenous Peoples on whose traditional ancestral territory we were gathered.

As settlers, we commit to making the promise of Truth and Reconciliation real in our communities, and in particular, to bring justice for murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls across our country.

Social Media

Connect with us on social media!

You can tag us on Twitter or Facebook:

Facebook: facebook.com/TheLearningNetwork

Twitter: @learntoendabuse

Connect with others about TBI and VAW by using the hashtag #VAWTBI

Learning Network Team

Linda Baker, Learning Director

Elsa Barreto, Digital Media Specialist

Dianne Lalonde, Research Associate

Robert Nonomura, Research Associate

Sara Mohamed, Research Coordinator

Anna-Lee Straatman, Project Manager

OVERVIEW

In recent years, a growing body of research in concussions and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) has become the subject of much public attention. Increased awareness of the short- and longterm health effects of neurological trauma has raised questions about the “unseen” effects that violence can have both in the body and in society more broadly. And while a considerable amount of research has investigated the prevalence of brain injuries in athletes and combat veterans, discourse among policymakers, the public, researchers, and even some service providers has been slower to address the occurrence of TBI in relation to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV).

This gap in awareness is an especially urgent one given the high proportion of women who have experienced IPV in Canada. Statistics Canada reports that one-third of all police reported violence involves intimate partners (95,704), that nearly 8 out of 10 of these victims are female, and that “violence committed by an intimate partner (45%) was the most common type of violence experienced by female victims of violent crime in 2017” (Brczycka 2018, pp. 22–27).

Considering the findings of a review by Ivany and Shminkey, which suggests that between 60–90% of women with experiences of IPV had also received blows to the head or neck (2016, p. 129), and what is known about how patterns and experiences of violence are shaped by social structural inequalities (e.g., Collins 2017), the relationship between IPV and TBI might be best understood not only as a matter of health policy but also as a social phenomenon that may take shape differently in relation to factors such as race, gender, sexuality, class, (dis)ability, age, citizenship, and so on.

Thankfully, this knowledge gap is currently being filled by a range of engaged and innovative support workers, researchers, survivors, educators, and knowledge translators whose work brings the empirical findings of neuro- and social science together with the trauma- and violence-informed insight of front-line service provision to enrich our understanding of how experiences of IPV and TBI may be understood and supported.

In order to more widely share this knowledge among stakeholders, as well as foster the ongoing development of interdisciplinary networks and insight, the Learning Network recently hosted a Knowledge Exchange addressing the connection between Violence Against Women (VAW) and Traumatic Brain Injury. The full-day event featured presentations from service providers, activists, survivors and researchers. The event was attended by over 130 people, representing a range of fields including Indigenous, Immigrant and Refugee, and general service projects in the violence against women, health, education, and justice sectors.

The event’s “Learning Objectives” for attendees were to:

- Identify the neurophysiological and behavioural elements of IPV and sexual violence (SV) related TBI

- Recognize the challenges TBI creates for women navigating services and daily activities

- Describe the relationship between TBI and the stress of violent experiences

- Understand how intersecting oppressions impact IPV and SV related TBI

- Describe barriers to recognizing and responding to IPV and SV related TBI

- Identify promising strategies for recognizing and supporting women experiencing IPV and SV related TBI

Presentations from Ontario-based organizations included:

- A demonstration of the Abused and Brain Injured Toolkit by Lin Haag, a Ph.D. Candidate at Wilfred Laurier University and trainee at the Acquired Brain Injury Research Lab, University of Toronto.

- A presentation by Dr. Flora Matheson whose survey research examined the intersection of TBI and VAW through interviews with women and transgender women doing sex work.

- An overview of the helpline, peer support, and educational support resources offered by by Ruth Wilcock and Vijaya Kantipuly at the Ontario Brain Injury Association.

- An address from Melanie Marsden of Springtide Resources on best practices for VAW support work and research involving people with disabilities.

- A panel of survivors chaired by Nneka MacGregor for the Women’s Centre for Social Justice (WomenatthecentrE), including Deirdre Reddick, Jeannie Quinn, and Winnie Muchuba. Invited speakers from outside Ontario also delivered presentations.

- Dr Eve Valera from Harvard University discussed some of the neurological and practical factors affecting the experiences and challenges of women who experience TBI.

- Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose from the University of Regina introduced a holistic, culturally responsive framework for supporting Indigenous and non-Indigenous women with TBI from a strength based perspective.

- Dr. Akosoa McFadgion from Howard University presented interview research and practical insight that challenged service workers to critically reflect upon the challenges Black women face in navigating their IPV-related TBIs.

- This report summarizes the wide range of subject matter presented by the speakers, as well as feedback shared by participants on the Knowledge Exchange’s content.

Comments from Knowledge Exchange Participants

“All speakers were very informative. The personal stories of their journey were heart felt real life experiences and tied in with the other presentations.”

“Really loved the presenters and knowledge shared. I applaud the organizers and the bravery and resilience of the survivors, and I am honoured to be a part of these women.”

“Absolutely wonderful Forum. Very interesting. Lots of information and new knowledge. Well-presented. Really packed day but so interesting and lively, one couldn’t help but take in everything.”

PRESENTATION SUMMARIES

TBIs and Strangulation: Understanding and Recognizing the Hidden Dangers of Intimate Partner Violence

Dr. Eve Valera

Dr. Eve Valera established a conceptual framework for how TBI is understood from a public health and a neurological perspective. As a starting point for understanding IPV-related TBI, Dr. Valera noted first the prevalence of IPV within society. IPV is the leading cause of homicide for women globally and the most common form of VAW. Dr. Valera estimates that among women with experience of IPV, 80–90% have sustained injuries to the head or neck, and that such abuse is often not just a single occurrence but a repeated pattern with cumulative effects.

Dr. Valera also explained the physiological process by which brain injuries are sustained, and how they affect the brain’s (and thus, a person’s) health and ability to function afterward. Because of the negative cognitive and social implications of these injuries, inquiries from researchers, medical specialists, and service providers may need to take special measures when conducting interviews (e.g., instead of “did your partner ever choke you out?” interviewers might ask, “after anything your partner did to you, did you ever lose consciousness, feel dizzy…?”). Dr. Valera also emphasized the importance of recognizing the extent and effect of post-concussive symptoms that individuals may face: post-concussive syndrome may last for weeks or months after an injury, and can entail headaches and dizziness, impaired judgment and memory, and aggression, anxiety, depression, or impulsiveness. When these occur in the context of IPV, they therefore stand not only as a detriments to a woman’s wellbeing but also to her ability to hold a job, adapt to living in a shelter, make and remember safety plans, and escape a potentially lethal situation for herself and/or her children.

Given the apparent immensity of this (as-yet) inadequately addressed issue, Dr. Valera concluded with an urgent call to action: “IPV-related TBIs are a public health epidemic in desperate need of being understood.”

Battered, Brain Injured, But Unbroken

Nneka MacGregor, Deirdre Reddick, Jeannie Quinn, Winnie Muchuba

The Ontario-based group WomenatthecentrE held a panel discussion in which survivors with experience of IPV and TBI discussed their insights and stories relating to this issue. The speakers addressed a range of topics that not only humanized the ways that IPV can often “hide in plain sight,” but also illustrated the resilience and courage that women embody in surviving it. For instance, in describing scenarios where she would take action in phoning for help, one presenter related:

“He would rip the phone out of my hand and beat me over the head with it. That’s how hard it is to leave.”

Drawing upon their experience in various forms of advocacy, support, and/or research on the topic of IPV and TBI, the participants were also able to illuminate connections between personal experience and social systems such as hospitals, law, and first responders. For instance, Ms. Quinn explained how experiences of trauma or brain injury can exacerbate the difficulty of navigating the gaps and loopholes of the current social service system. Ms. Muchuba spoke of the influence that in some countries cultural shame can have on an individuals’ willingness to leave an abusive partner, an observation that the moderator, Ms. MacGregor, confirmed is present in Canada as well.

When invited to share one word of advice to individuals currently experiencing IPV while dealing with potential TBI, the participants offered:

“Listen” “Believe” “Respect” and “Talking is therapeutic—speak up!”

In the later Question and Answer discussion, the panel also offered a number of practical suggestions for service workers. Ms. Macgregor offered that taking efforts to be a patient, kind, non-judgmental ally to survivors is not just a humane way to act, but it also has the practical benefit of lowering stress levels and enabling the interaction to work more effectively. Ms. Reddick pointed out that a practical consideration that can go a long way is having paper available so that a client can take their own notes to help them remember important topics from an appointment. To this suggestion, Ms. Quinn added that individuals with a TBI may be slower at taking notes, and so speaking and covering ideas more slowly can be helpful, as can providing leaflets or information cards. Above all, however, she urged service providers to acknowledge the validity of survivors’ testimony, and to support it:

“Believe us. Respect that we are telling the truth. It did happen that way.” Jeannie Quinn

An Indigenous Perspective on TBI and VAW

Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose

In the morning section of her two-part presentation, Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose outlined the key conceptual features of an Indigenous framework for understanding TBI and IPV. These included:

- A strength-based health model, capable of emphasizing the available assets and capacities of the community, the land, and the leadership, rather than only the negative factors.

- Family focused care that incorporates not just an individual’s needs but the family’s as well.

- An historical recognition of the colonial context that shapes health in Indigenous communities (including the effects of residential schools, intergenerational trauma, and relocation and confinement).

- A relational worldview, including principles of “cultural responsiveness”—the capacity to respond to the needs of diverse communities, individuals, landbases, and cultures from a position of love and respect.

Although this framework has been developed by Indigenous Peoples and with specific concerns of Indigenous Peoples in mind, Dr. Sasakamoose pointed out that the framework remains adaptable to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities alike. However, it also stands as a critical challenge to some of the prevailing Western assumptions about health and Indigenous communities. For instance, Dr. Sasakamoose problematized the way that a notion such as “closing the gap” between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health posits the latter as the benchmark for “good health.” Moreover, this notion takes for granted a Western definition of health, which centres its objectives around the absence of disease, while minimizing considerations of community health and wellness.

Dr. Sasakamoose emphasized the need for a paradigm shift away from a reactionary Western model of health delivery toward an adoption of Indigenous-led health policy that reflects a holistic, preventative approach to spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical well-being.

Manifestations in the Lives of African American Women: IPV and TBI

Dr. Akosoa McFadgion

Dr. McFadgion’s presentation drew upon her qualitative research to help clarify the complex ways that individual, cultural, and social factors can shape people’s experiences with IPV and TBI. In particular, she described how her participants would frequently attribute symptoms of TBI with other causes (e.g., “it was just a situation I was in”), but explained how this retention of personal autonomy may be complicated by the effects that TBI can have on employment, health, and one’s ability to cope with stressful situations: “I’m almost stuck in my tracks.”

Additionally, Dr. McFadgion presented a list of critical themes to consider when engaging with clients who have experienced TBI and IPV, such as:

- Intergenerational trauma and the historical processes by which social inequalities, oppressions, and structural/social violence comes to affect individual well-being.

- Limitations in attention span, and the value of using repeated practices and context-centred cognitive rehabilitation.

- Irritability and aggression—symptoms of TBI which can sometimes be mistaken for mental illness.

- Information processing, as a crucial factor in ensuring that her experiences and perspectives are being recognized and supported.

Dr. McFadgion’s discussion of these themes was illustrated with a range of quotations from research interviews with women who had experienced IPV-related TBI. In this way, she showed not only how symptoms of TBI can manifest, but also the dynamic “strategy codes” by which her participants sought to navigate these challenges. These strategies ranged from writing down notes, to prayer and spirituality, to finding inspiration in one’s children or in oneself. Such codes may thus become valuable sites for

support workers to help empower their clients by working together in finding ways to cope, learn, and grow from the challenges they face.

Head Injury Among Women and Transgender Women Doing Sex Work: What We Know

Dr. Flora Matheson

In her presentation, Dr. Flora Matheson described TBI as a “silent epidemic,” affecting 10 million people globally. She explained that within the available research on this topic, sex workers remain a significantly understudied group. Her research therefore consisted of interviews of women and transgender women engaged in sex work in Toronto and sought to understand the lived experience of the intersection between sex work, gender-based violence, and TBI (Baumann et al. 2018.). As Dr. Matheson explained, her interview approach proved highly effective since she was able to ask the participants for stories about their experience and to then build on these, rather than relying solely on diagnostic tools. Interviewees in the study helped to illuminate several important patterns for service workers, policymakers, and first responders to consider moving forward:

- Fear of seeking medical attention: The stigma surrounding sex work leads individuals who do require medical assistance to sometimes give untrue accounts of how they were injured (e.g. they attribute injuries to a drunken altercation or a fall instead of violence experienced at the hands of a client).

- Negative encounters with police: Unfortunately, there remains considerable stigma and mistreatment toward sex workers by police, even in cases where they have been the victim of a violent crime. Interviewees describe feeling judged by police, being treated disrespectfully, and receiving questions about what they were wearing at the time of an attack (Baumann et al. 2018).

- Power in numbers: Although many did not feel comfortable reporting perpetrators of violence individually (for reasons such as the ones stated above), the participants did express a sense of power in collective action, where fellow workers were able to come forward and corroborate a pattern of incidents.

Working with Women Who Have Sustained IPV-Related TBI

Dr. Eve Valera

Dr. Valera’s second presentation expanded upon the theoretical and empirical materials of the morning session to address more specific aspects of working with women with experiences of IPVrelated TBI. The main focus of this presentation was identifying and navigating obstacles to providing/receiving support.

She noted that women will visit an Emergency Room for a variety of reasons (bleeding, broken bones, etc.), but a brain injury is rarely one of them. Because brain injuries often show no visible signs, and a woman might not necessarily realize or evaluate the TBI, these injuries often go unreported and thus untreated. This is likewise the case for strangulation, which also often shows no visible signs of injury (she described a study in which only 15% of women had photos of external injuries from strangulation that were of sufficient quality to be used in court). Strangulation also tends to go unreported unless effectively prompted in interviews. For example, women experiencing IPV rarely reported being “strangled” and only sometimes report being “choked” but do report situations in which “he put his hands on my neck,” “he put his arm against my throat,” or “he pinned me against the wall with his hands on my neck.”

The presentation also addressed the fact that in cases of IPV, women’s recovery factors for healing a TBI are often compromised. IPV causes significant psychological distress—both general life stress and acute intense bouts of stress—and therefore curtails the kind of brain rest needed for individuals to recover and engage in daily tasks. Compounding this effect is the presence of other forms of physical damage that may have been sustained, which consume the body’s resources to heal as well.

TBIs Are Often Misinterpreted Or Missed

The impacts associated with TBIs overlap with the symptoms associated with other problems (e.g. depression, anxiety, intoxication, PTSD). Consequently, TBIs are often missed.

A woman with a TBI may experience:

- confusion

- attention difficulties

- headaches

- dizziness

- coordination problems

She may appear:

- confused

- uncooperative

Dr. Valera reiterated how symptoms like disorientation, confusion, and inconsistent memories may have considerable practical consequences. An individual speaking with police, for instance, may appear inebriated, or provide an inconsistent account of events due to their brain injury. In a clinic or shelter, they may appear irritable or bad-tempered. She noted that the Brain Injury Alliance’s HELP Screener tool, could serve as a more general (non-medical) means of ascertaining whether or not an individual may have experienced a TBI.

Dr. Valera concluded with a number of emphatic points on the value of empowerment, the importance of providing respectful feedback on problem areas, and utilizing the available skills and resources at one’s disposal to encourage self-determination and identify strengths.

Healing from an Indigenous Perspective

Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose

Building upon her morning presentation Dr. Sasakamoose delved into the main factors comprising a “Culturally Responsive” approach to addressing issues of IPV and TBI. As she explained, this approach derives fundamentally from Indigenous ways of knowing, but is nonetheless applicable to issues facing non-Indigenous Peoples as well. This “two-eyed seeing” approach entails a cooperative way of building upon the strengths of Indigenous and Western knowledge and using these together to address important issues. The factors within this framework are:

- Taking a spiritually grounded approach. This entails research practices that involve Indigenous worldviews and holistic views of wellness; that foster connectedness to family, the community, and the land; and that use ceremony, traditions, and cultural practices.

- Developing a plan and perspective that is community specific and based in the community’s strengths rather than the prior objectives or assumptions of researchers. In this way, research may support initiatives that take direct account of the community’s own vision of its needs, capacities, and interest in engagement.

- Adopting a trauma informed perspective that accounts for the intergenerational effects of colonization and the kinds of inequalities and distrust that this system has wrought. Here, Dr. Sasakamoose drew upon a particularly striking quote concerning the legitimate distrust that Indigenous Peoples may have toward Western health systems and governmental programs:

“When they talk about ‘healing’, they forget how that word can sound to people who were abused in residential school. Who is going to want to go to the abusers for healing? No thank you!”

(Carlson & Steinhauer, 2013, p. 24). - Drawing upon strength-based approaches to meeting challenges through a range of empowering methods:

- Identifying individual resources and abilities that a person has

- Emphasizing resiliency and strength

- Providing resources that invest in the long-term well-being of communities and individuals

- Artistic expressions

- Focusing on “what makes us well?” rather than “what makes us sick?”

- Arranging settings in offices, institutions, schools in ways that promote well-being and healing

Concussion Hits Home

Ruth Wilcock and Vijaya Kantipuly

In keeping with the afternoon’s focus on practice and support services, presenters from the Ontario Brain Injury Association (OBIA), Ms. Ruth Wilcock and Ms. Vijaya Kantipuly, shared an overview of some of the organization’s ongoing programs. OBIA has been working for over 30 years to serve individuals who have experienced brain injury.

One of OBIA’s current programs, Concussion Hits Home aims to bring greater awareness to the issue of concussions and domestic violence. The project involves peer support programs that match individuals of similar ages, life experiences, and genders, and bring them into contact with one another to help build support and social connections for navigating the challenges of brain injury. OBIA has also developed an online support group system for clients, which contains curriculum-based, topic focused, and online open-forum components to support a range of possible needs among clients.

Overall, these programs provide a twofold benefit of client care (by reducing isolation, providing emotional support, and providing a “safety net” for those who have nowhere else to turn) and knowledge translation (by supporting clients in a field where very little support is otherwise available). Indeed, as Ms. Wilcock and Ms. Kantipuly noted, these imperatives are “the bridge that connects medical teams and community”.

Thus far, these programs appear to have been highly successful, with 93% of participants reporting that they gained emotional support from the peer group, and 71% saying that their knowledge and coping skills had increased.

OBIA also offers a toll-free helpline for individuals who wish to discuss issues and feelings relating to loneliness/isolation, invisible disability, income supports, Caregiver Supports, and other social services such as legal and financial assistance, housing, employment, or transportation: 1-800-263-5404.

Best Practises for Inclusion for People With Disabilities in the VAW Sector and Research

Melanie Marsden

As a representative of Springtide Resources, Ms. Melanie Marsden delivered a poignant address on inclusive approaches to meeting the needs of clients experiencing IPV-related TBI. Her talk posited an ethical “duty to accommodate” in the form of providing appropriate representation, compensation, and influence to otherwise marginalized individuals or groups. Such inclusivity, she argued, must go beyond ceremonial or token recognition. It should instead be demonstrated in real-world follow-through on the issues and needs they raise.

For instance, she noted the fact that Indigenous Peoples will often be asked for their opinion on an event, service, or project, only to have the exact opposite course of action take place. This failure in listening and follow-through not only disrespects the speaker; it also makes them less likely to engage in future initiatives. As Ms. Marsden explained, this process can also be seen in the broader context where marginalized individuals hesitate to report IPV to police or support workers, for fear that they will likewise be dismissed or underserved.

Thus, matters of accommodation have especially high stakes when IPV and TBI are involved. Ms. Marsden urged that in such circumstances, “we’re the experts of our lives. We know what we need and what we want,” and that support workers must recognize this authority. As an example, she pointed out how a person with a disability living in an abusive relationship cannot simply pick up and leave to go to a shelter, as an outsider might assume. Rather, they face a range of considerations such as whether the shelter will have adequate support resources and whether their story will be believed (Lalonde & Baker 2019). Because such real-world considerations may not readily come to mind for a support worker or researcher who has not lived this same situation, it is imperative that decision-making processes be inclusive and accommodating of individuals with a wide range of social and personal experiences. A helpful “starting point” resource that may be of interest to readers who wish to meet this “duty to accommodate” is the Springtide Greeter Guide, linked here: https://www.springtideresources.org/sites/all/files/Working%20Together%20-%20A%20Guide%20to%20Developing%20Good%20Practice.pdf

Unforeseen Barriers: Interventions for Women in Shelter

Dr. Akosoa McFadgion

This presentation addressed many of the themes presented so far throughout the afternoon and expanded particularly upon the practical impact that service workers have in the domain of IPV-related TBI support and recovery. The discussion was framed in terms of a “Synergy Framework” that places central importance upon the interconnection between individuals and community. In contrast to a “Logic” Model, which functions as a (supposedly) rational assessment of means, ends, and available resources, or a “Process” Model, which documents the effectiveness of a program on the basis of outputs (e.g., types of services provided, the number of women served, or the number of job interviews a client attended), the Synergy Framework provides a culturally-sensitive approach that seeks to fulfill broader values and includes a wider perspective of how support and healing may take place.

In particular, it draws upon certain African-Centred strategies appropriate for implementing trauma-informed programs in partnership with communities of colour. For instance, the Synergy Framework encompasses both individual factors like cultural identity, self-knowledge, and selfreliance, and collective experiences such as collective identity, fundamental goodness/reciprocity, and spirituality. Furthermore, it regards these factors as mutually constitutive and potentially liberatory:

“You have to be able to highlight the consciousness among survivors that intersects racial, cultural, and economic influences in a unique experience of trauma.”

—Akosoa McFadgion

Dr. McFadgion explained that this perspective provides a means for drawing insight from the interconnections among individual, collective, and spiritual experiences—insight that can be put to practical use in serving and relating with others. In this way, she argued, “collective identity is always the source of individual identity,” and “communal liberation gives way to individual liberation.” In light of this perspective, she offered a number of ways that the “unforeseen barrier” posed by service workers themselves, may be transformed into opportunities for more mutually productive relations with one’s clients.

Introducing the Abused and Brain Injured Toolkit: Understanding the Intersection of Traumatic Brain Injury and Intimate Partner Violence

Lin Haag

In the event’s last presentation, Ms. Lin Haag presented a web-based toolkit developed in connection with Women’s College Hospital, WomenatthecentrE, Women’s Habitat, the Cridge Centre for the Family, the Acquired Brain Injury Research Lab at the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. This program is designed to build links among people with various abilities and skills pertaining to the research and support of IPV-related TBI. It also aims to facilitate service providers in adapting their work to the wave of demand relating to this issue. Ms. Haag’s research finds a preponderant lack of previous training on recognizing TBI among IPV survivors, as well as a tendency to underestimate the prevalence of TBI among the client population.

And indeed, the stakes and the practicality of many protocols for TBI, such as those developed for athletes, are simply not always feasible for women facing IPV. As Ms. Haag notes,

“We tell athletes (who suffer head trauma), ‘don’t get back into it for a year, don’t get injured for two years.’ You want to tell these women that? It’s not realistic.”

There is therefore an urgent need for developing effective training and support systems for survivors of IPV experiencing TBI. Especially important is the need to ensure that TBI diagnoses are not used unscrupulously as a “weapon” against survivors themselves. Given the symptoms of TBI discussed in several of the presentations (memory loss, mood swings, etc.), there exists a negative possibility that a TBI diagnosis may be exploited by the abusive partner as a form of gaslighting, or in courts as a means of diminishing a woman’s credibility. Inspite of these challenges, Ms. Haag offered a compelling argument for women’s rights to know what is going on in their bodies, and the concomitant duty of support workers and researchers to answer the call for greater public awareness of the factual and ethical implications of this issue. That is, a duty to show that “women who have brain injuries are not incompetent, they’re not incapable; they just need a little understanding and a little bit of flexibility from you” — and, perhaps also, a commitment to fostering a more rigorous public and professional discourse around the relationship between IPV and TBI.

Summary

Given the way that IPV-related TBI “hides in plain sight,” both as a personal challenge for individual women but also as a broader public issue for service workers, the Knowledge Exchange carried a dynamic sense of intellectual discovery, collegial supportiveness, emotional gravity, and moral determination to face the personal and public challenges posed by this issue. It is important to once again highlight the recurring theme of empowerment, positivity, and solidarity that characterized the presentations and discussions, especially considering such serious topics as brain injury and gender-based violence. As attendees expressed in their written feedback, “although (they addressed) a very heavy topic, all speakers were uplifting and amazing,” making for “a wonderful day of learning and knowledge.” What follows is an overview of responses shared by participants regarding their personal evaluation of the forum’s contents as well as their suggestions for areas of further development and exploration.

Comments from Knowledge Exchange Participants

“Such a refreshing change to hear deep respect for the service users.”

“It is so knowledge-packed, this event could easily be 2 days. The speakers are knowledgeable, it is worth way more than we paid.”

“What a fabulous experience! this has reinforced my passion and has left me feeling hopeful and empowered. I was in tears throughout this event, not because I was sad, but because of how powerful it has been. thank you. It made us feel as though our work is important when policies discourses tell me otherwise.”

Participant Feedback

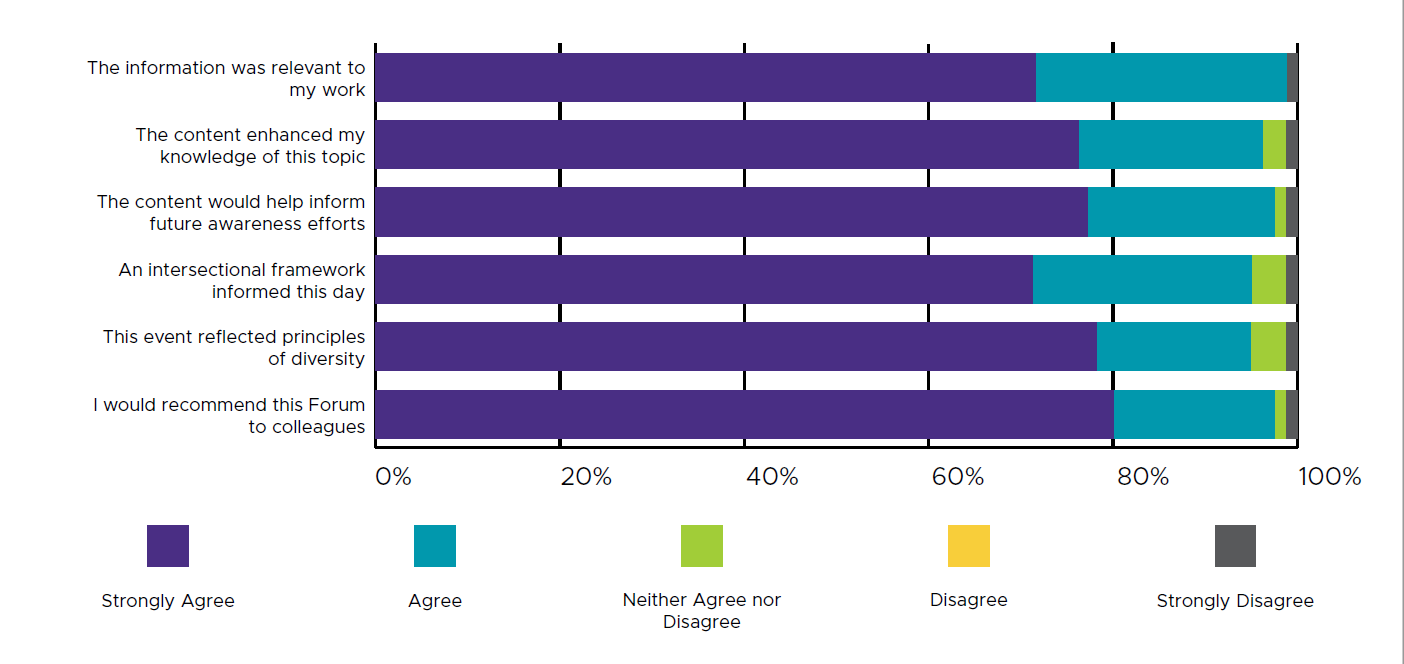

Anonymous surveys inviting both written and questionnaire feedback were distributed to participants at the conclusion of the Forum. The responses collected (n=81) reflected the exceptionally positive level of engagement that took place throughout the day. In each of the six questionnaire categories addressed, over 95% of participants expressed either “agreement” or “strong agreement” about the value of the day’s materials (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of Evaluation Responses for Items in Learning Exchange

Feedback Survey (n=81)

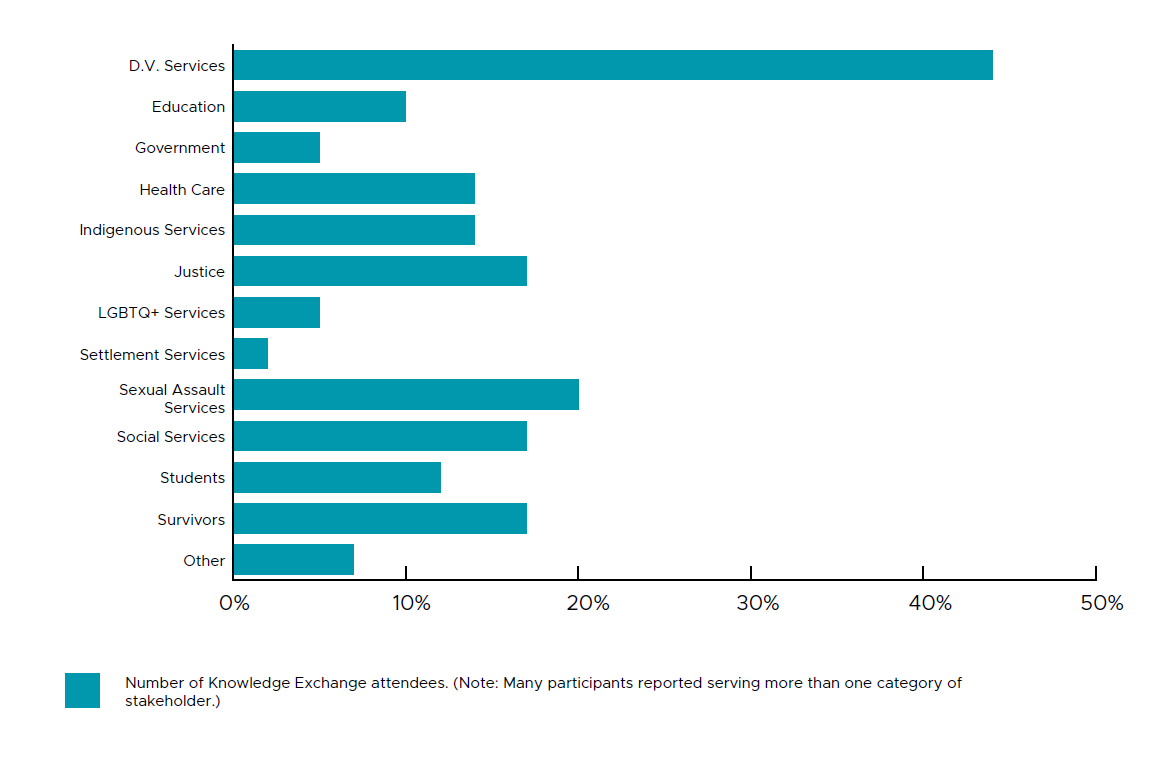

The event’s attendees represented a broad range of service sectors, and often served multiple stakeholders simultaneously. In order to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of this work, and to ascertain which sectors would be most impacted by what participants had learned, the feedback survey invited participants to specify all the applicable stakeholders that they served (i.e., rather than requiring them to specify a single field). Figure 2 presents the number of attendees who will be bringing the event’s information back to various sectors.

Figure 2: Stakeholders Served by Knowledge Exchange Attendees (n=81)

Areas for Deeper/Future Exploration

Participants offered a considerable amount of valuable feedback on the Knowledge Exchange. These suggestions have been thematized into two categories below: recommendations for enhancing K.E. programming and ideas for future directions for expansion and collaboration.

Programming

- Participants consistently expressed appreciation for the inclusivity reflected in the event’s speakers list. One suggested area for further elaboration was to expand on the circumstances of IPV and TBI among LGBTQ2S individual. Given some of the possible differences in power dynamics within same-sex relationships, the available services and supports, and the effects of social stigma, a further examination of how TBI might be experienced and navigated in the case of partner violence in LGBTQ2S relationships remains a viable topic of future exploration.

- The presentation style of many speakers was very positively received by attendees, as was the allocation of time for audience questions to the panels. Some participants expressed that the event could have been enhanced through some additional interactive programming as well, such as hands-on, roundtable, or group discussions.

- Requests for the presenter slides were also expressed by some participants. Some stated that they would have found the slides useful in following along with the presentations, while others requested copies of the slides after the event so that they could revisit interesting pieces of information. With the permission of the presenters, the Learning Network met this request by providing registrants a link to the slides following the Forum.

Expansion and Collaboration

- As noted in the overview of “Stakeholders Served” by the participants (Figure 2), 17 attendees served in justice and first responder fields, and five in government. Given the ways in which TBI symptoms (e.g., disorientation, memory loss) may adversely affect an individual’s perceived credibility before the legal system, many participants suggested that it was vital for these fields to learn more about the connection between IPV and TBI. As one participant offered, “TBI presents particular challenges in family litigation—perhaps a conference aimed towards law practice in this case.” Future Learning Network projects or collaborations might therefore seek to engage directly with police, first responders, and members of the legal system (e.g., family and criminal courts).

- The current amount of public attention on the effects of concussions in sports was raised as a point of contrast to TBI in IPV survivors by several presenters. As one participant suggested, this situation may provide a useful opportunity for partnering with sports teams or leagues (e.g., CFL, NBA, NHL) to raise awareness of the ways TBI can affect survivors of IPV.

- Enthusiasm for expanding the audience for this issue across a range of disciplines and publics was consistent among participants.

A FINAL THANK YOU

We would like to once again express our sincere thanks to all participants and presenters, particularly Dr. Gloria Alvernaz Mulcahy for leading us in an opening and closing song. We wish to also offer thanks to the colleagues of attendees who were perhaps unable to attend but whose work nonetheless contributes to an ongoing struggle against gender-based violence!

As knowledge of the relationship between IPV and TBI continues to grow, collaboration and dialogue among researchers, service providers, advocates, and women with lived experience of IPV and TBI will become all the more essential. The Learning Network is currently working on several Ontario-based resources to contribute to these important developments. Subscribe to our mailing list for further content in the coming months: www.vawlearningnetwork.ca

REFERENCES